The following is a reposting of a somewhat lengthy Medium article of mine from about 6 years ago, partly to update some dead links and do some light editing, and partly to add some clarifications (I hope) and late-breaking news. And partly because I hope this will serve as a bit of a preamble to a (hopefully) forthcoming review of ’s Material Girls.

And an important reason for the last point is that Stock’s perspectives on the definitions for both sex and gender have changed somewhat over the years, generally for the better, and the following may serve to emphasize that evolution and the reasons for it. Even if she still drops the ball somewhat short of the goal line on both concepts — particularly in her apparent misunderstanding of the nature of “homeostatic property clusters” since the presence of the homeostasis process or phenomenon is essential. For example, see this bit from her Duke Law post on “The Importance of Referring to Human Sex in Language”:

“An alternative theory of the sexes, which I do not have space to consider here, construes the sexes as two homeostatic property clusters with no necessary nor sufficient conditions for membership of each.”

https://lcp.law.duke.edu/article/the-importance-of-referring-to-human-sex-in-language-stock-vol85-iss1/

Unfortunately, what she is talking about there, absent the homeostasis, boils down into the sexes as spectra – politics, strange bedfellows, and unintended consequences. A potentially useful point of reference on that topic:

https://joelvelasco.net/teaching/systematics/boyd%2099%20-%20Homeostasis%20Species%20and%20Higher%20Taxa%20(draft).pdf

But in addition to her discussions of sex, while she provides a useful and workable definition for gender identity — something which didn’t figure directly in my Medium post much beyond the question of “identifying as X” — what seems missing is any coherent definition for “gender” in the first place.

But one other thing of note in her book, dovetailing with her Duke Law post, is that she broaches the important philosophical concept of natural kinds — i.e., “groupings that reflect the structure of the natural world rather than the interests and actions of human beings” — and provides some practical examples and discussion of the concept.

Finally, as something of a point of clarifying information, some time after writing that Medium article I had run across a definition for “identify as” that may shed some light on the title and the issue in general:

identify as, phrasal verb;

identify as something: to recognize or decide that you belong to a particular categoryThe thing there is that someone can’t just arbitrarily “decide” to belong to, or insist they’re a member of a particular category. For example, someone who’s 45 can’t “decide” or insist they belong to the category “teenager” — at least without being taken as madder than a hatter — since that requires one to be 13 to 19 years old. Likewise with transwomen who can’t arbitrarily “decide” they belong to the category “female” since that category generally requires one to at least have some ovaries which, of course, no transwoman will ever have.

But, without further ado:

*******************************

Recently there’s been a spate of articles by several feminist philosophers and science writers of various stripes who have bravely, and somewhat commendably, made an effort to define the category “woman” to deal with several thorny and contentious social issues. And chief among the more clearly delineated of those articles is a Quillette post [Ignoring Differences Between Men and Women Is the Wrong Way to Address Gender Dysphoria] by philosophy professor

, although one at Aeon [The woman subject] by political science professor Georgia Warnke, and another [Decoupled from reality] at “Weekly Worker” by science journalist (?) Amanda MacLean also provide some useful illumination and perspectives.And there can be little doubt that there is a great deal of justification for those efforts — as Stock puts it, there is “a distinctive form of inequality directed at females as such, by virtue of their belonging to the category of people associated with the burden of reproduction”. There is quite clearly an obvious “asymmetry” in that process based on, as MacLean puts it, an “enormous difference in reproductive investment and reproductive risk” that justifies fashioning some precise language as a way of grappling with the social consequences of those differences. And the first two articles at least usefully broach the topic of categories — a topic on which there is a great deal of “problematic” confusion — in sufficient detail so as to provide us with some useful tools and starting points to do that fashioning. In addition, they will help us to address the consequential and equally problematic sex-as-a-spectrum [SAS] “thesis” promoted, if inadvertently, by Stock in particular as well as to address, to a lesser extent, the problematic aspects of the conventionally scientific anti-theses from the sex-as-a-binary [SAB] camp which is, in turn, exemplified by an article, The New Evolution Deniers, by evolutionary biologist

.However, all three of those authors more or less exhibit what might be construed as a fatal flaw in championing an analytic and logical approach to defining the terms “woman” and “female” — quite justifiable in itself — while, at the same time, seeking to retain and promote a notably emotional if not wooish aspect to it that is, in their subjectivity, largely untenable and highly problematic. As the philosopher & lawyer Elizabeth Finne put it, echoing her Quillette post on the tyranny of subjective narratives, “We live in a brave new world in which the subjective is regarded, in some ways, as representing a higher sort of truth than any objective propositions we can get broad agreement on.” All fine and dandy to at least genuflect in the direction of “lived experience”, but, as it’s difficult to adjudicate between different subjective experiences, it seems best to promote either objectivity — not least because of its success in the scientific realm — or at least a somewhat subjective consensus, as flawed as each of those may be in themselves.

And an excess of that subjectivity seems to vitiate much of feminist philosophy which in turn frequently seems driven more by emotion and peevishness than by reason and logic, ranging from philosopher Sandra Harding’s characterization of “Newton’s Principia Mathematica as a ‘rape manual’ …” to philosopher Luce Irigaray’s critique of “the privileging of solid over fluid mechanics”. As philosopher Noretta Koertge argues, “Unfortunately, the predominant feminist response has been to attack logic and other traditional canons of rationality as sexist.” No doubt, as a review of Koertge’s & Patai’s “Professing Feminism” puts it, that attitude is, in part, the result of “the virulent anti-science, anti-intellectual sentiment driving many of the professors, staff, and students” in various Women Studies programs all across the land.

So, for all the undoubted and quite justified compassion all three of those authors exhibit, it’s hard not to get the impression that they’re all putting the cart before the horse — some further ahead than others — and further paving the road to hell with their good intentions. And, more specifically, Stock in particular, while commendably accepting that we can’t reasonably go “to a conclusion about the nonexistence of material sex”, still opens the door — by intent or inadvertently — to the highly problematic and largely untenable claim that sex is a spectrum.

For instance, Stock states quite explicitly that, for her, “there is no hard and fast ‘essence’ to biological sex, at least in our everyday sense: no set of characteristics a male or female must have, to count as such.” And that is more or less what “professor of biology and gender studies” Anne Fausto-Sterling argued in a New York Times article (archive link) of 2018 that: “… there is no single biological measure that unassailably places each and every human into one of two categories — male or female”. And that is, similarly, the essential argument of science journalist Claire Ainsworth in her “Sex redefined” article in the “prestigious” journal Nature, although MacLean at least gives a largely credible and cogent critique of Ainsworth in particular and of the “woman subject” in general; more of which later.

But, in addition to hanging out her shingle as a “spectrumist”, Stock undergirds and gives some weight, if more apparent than substantive, to that spectrumist claim, while more usefully broaching the seminal question of categories by touting philosopher Alison Stone who has argued that “the concept of biological sex is what philosophers call a ‘cluster concept’ … determined by possession of most or all of a cluster of particular designated properties ….”

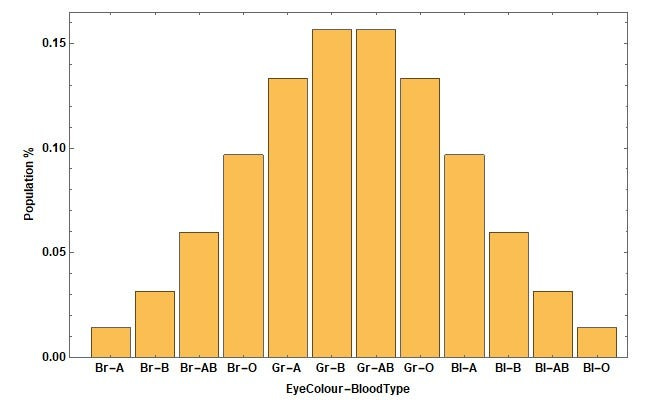

And, as an illustration and one consistent with Stock’s “spectrumist” thesis, we might assert — imperiously — that an as yet unnamed human category is defined by various clusters or combinations of two essential subcategories, requiring an instance or member from each class or subcategory. For example, we might have an eye-colour {brown, green, blue}, combined with a blood-type {A, B, AB, O} which yields a total of 12 possibilities (combinations or clusters) in the spectrum [Br-A, Br-B, Br-AB, Br-O to Bl-A, Bl-B, Bl-AB, Bl-O]. And we might then determine what percentage of the total population manifests each of those 12 possible combinations or clusters, and ask how they correlate with, and contribute to the existence of, various other attributes and behaviours:

So what is shown or suggested above is then that there are 12 different clusters (combinations) of specific traits, each of which grants membership in the “EyeColour-BloodType” category or spectrum (range) of subcategories. Like the colours in the visible spectrum.

So the “cluster concept” clearly has some utility, as does the more general concept of categories in the first place. As Steven Pinker quite cogently noted:

“An intelligent being cannot treat every object it sees as a unique entity unlike anything else in the universe. It has to put objects in categories so that it may apply its hard-won knowledge about similar objects, encountered in the past, to the object at hand.” [How the Mind Works; Steven Pinker; pg. 12]

But while the concept of categories and the principles behind them can be quite obscure and convoluted — the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy lists over 1000 articles thereon — the essential elements are more or less easily discerned while still retaining a great deal of their utility. As the Wikipedia article on categorization puts it:

For humans, both concrete objects and abstract ideas are recognized, differentiated, and understood through categorization. Objects are usually categorized for some adaptive or pragmatic purpose. Categorization is grounded in the features that distinguish the category’s members from nonmembers. Categorization is important in learning, prediction, inference, decision making, language, and many forms of organisms’ interaction with their environments.

But, given the general utility of categories, that then raises the somewhat thorny question — although the “one of the hour” — as to whether the sex category itself is, or should be, a spectrum based on a “cluster” of multiple subcategories — each comprised of multiple possibilities (“class members”) — genitalia, chromosomes, and gonads for example — or whether it is, or should be, based on a single “subcategory” of only two possibilities, of two members. So it seems the best way forward, the best way of answering that question is to start by asking ourselves, “what is the overriding or guiding” “adaptive or pragmatic purpose” that we should be following?

And in the case of “Taxonomy (biology)” — “the science of defining and naming groups of biological organisms on the basis of shared characteristics”, clearly a case of categorization writ large — it seems that the motivating purpose or objective is, to a large degree, to reflect the evolutionary history of the various species captured by the hierarchy of the sub-categories defined by that discipline — from species to family to phylum to life. But in the case of the “woman subject” which seems to motivate many feminist philosophers, the objective or purpose seems less one of fundamental scientific principles and logical rigor — see Koertge — than one, as Warnke puts it, of “an ‘ameliorative’ definition of women” which is designed to facilitate “emancipating women and ensuring their equality or … overcoming sexist oppression, and correcting disparities in power and privilege”. However, as admirable as those objectives may well be, such definitions and criteria — as even Warnke isn’t so far gone or so dogmatic as to fail to see — are rather subjective and highly context-dependent: the last Queen of England was hardly “subordinated” or in need of much “emancipation” and so, by the suggested “definition”, not entitled to claim membership in the exalted category “woman”.

Now such feminist philosophers are certainly entitled to create their own rather idiosyncratic, and largely inconsistent definitions and categories, even going so far as to use existing words such as “male” and “female” — at least if they can pay the words extra as Humpty Dumpty put it. However, when such definitions and categories start to conflict with or supplant the more traditional and more credible scientific ones (more of which later) — as has clearly happened with the questionable article at Nature by Ainsworth — and, as a result, produce no small amounts of unnecessary animosity and grief — as with badly-served dysphoric and autistic children — then maybe we should start asking ourselves whether there are flaws in both the traditional scientific categories, and the “new, improved!” versions from feminist and “progressive” philosophers and biologists. Maybe the “pragmatic purposes” that have motivated the creation of each set of categories, or their applications or uses, are, in one way or another, badly if not fatally flawed, maybe even in similar ways?

And while I’ll argue that the feminist versions are generally less tenable than the “scientific” or “folk-biology” ones, where the former goes off the rails and into the weeds — and in a rather spectacular fashion — is also, largely, where the latter does so as well, although not quite so obviously even if, apparently, for some similar reasons. Consequently, it will be instructive to analyze the former case in some detail, and then apply it to the latter. And the tool of choice to do that will, to start with at least, be the rather insightful observations provided by MacLean in her aptly-titled article, “Decoupled from reality”.

However, as MacLean has said a real mouthful or two which will require some serious “unpacking”, it will be useful to quote the crux of it, the high points of her argument to start with. Although it should be noted, for future discussion, that she too — with both Stock and Company, and with many in the sex-as-a-binary crowd — shies away at the last hurdle, apparently letting her vanity get the better of her reason. But, to wit:

a) The ‘spectrum of sex’ case is summed up in the news article, ‘Sex redefined’, by science journalist Claire Ainsworth …;

b) But what Ainsworth fails to do from the start is to explain what we are really talking about when we talk about the sexes;

c) Like many others in the gender debate, Ainsworth plunges directly into a discussion of the complexities and confusions around sex without first defining her terms;

d) Reductionist disciplines that look at different parts of organisms — such as genes, tissues, physiology or neurobiology — use the words ‘male’ and ‘female’ as shorthand for ‘of males/females’ or ‘typical of males/females’;

e) In ‘whole organism’ disciplines, sex relates to an organism’s potential reproductive role: to produce sperm (male), or to produce ova (female);

f) … there is one biological parameter that takes over every other parameter — it is the definition of sex that applies to the whole organism: its potential reproductive function.

And it is that “first defining her terms” which is the crux of the matter, and which is, in turn, specifically the “naming of biological organisms on the basis of shared characteristics” which are the sine qua non of categories. One is a member of a category because one has or exhibits the characteristic that defines that category. Now the process of naming is a bit of a thorny issue in itself — for example, see Kripke’s Naming and Necessity which Stock has cogently commented on recently — although that is generally well outside my salary range. But there are a number of salient points which can, again, be readily discerned, and which provide some useful points of reference.

And foremost among those points are the ideas about the axioms of a system of logic — i.e., those which are not deductively provable within that system — and about the system’s a priori tautologies or definitions — “All bachelors are unmarried” for example — which are “true”, by definition, because we assert, as a first step, the equivalence of the words (“bachelors”) and the states or properties denoted (“unmarried”). And, given those a priori definitions, there is simply no necessity, and it would show ourselves to be manifestly “unclear on the concept”, to then argue or even suggest that those definitions, or their creators, thereby deny anyone’s humanity; or promote the oppression, subjugation, or “privileging” of the category members so described.

In addition, as MacLean cogently notes or suggests, “in whole organism disciplines” the terms “male” and “female” denote ONLY the abilities — of the organisms themselves — “to produce sperm, or to produce ova” as the essential elements in the “reproductive role”. Which then ties-in-with or justifies her earlier comments about “different parts of organisms”: male genitalia, and female brains are that because they are, respectively, the genitalia of males and and the brains of females. Why, as she later suggests, talking about “the brain of a woman in the body of a man” is incoherent twaddle: if the organism produces sperm then, ipso facto, its brain is that of a male, even if it may happen to exhibit traits or aspects more typical of female brains.

Although those cases do help to emphasize and illustrate the confusion — and the unnecessary and quite counter-productive animosity — that that ambiguity in the use of language causes. As Francis Bacon — an early progenitor of the scientific method — put it many years ago: “Therefore shoddy and inept application of words lays siege to the intellect in wondrous ways.”

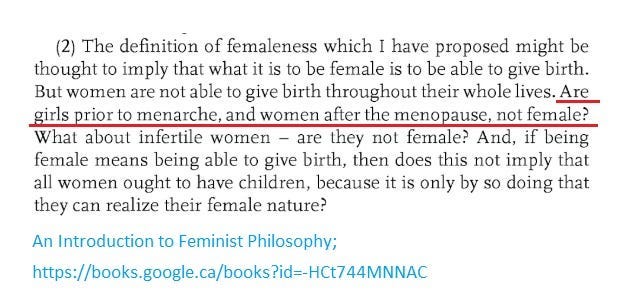

But one place in particular where MacLean diminishes her claims to fame and fortune is in somewhat evasively talking about “potential reproductive role” which thereby muddies the waters of what it means to have a sex, to be male or female in the first place. Particularly when the online Oxford English Dictionary (OED) — one of the more coherent, credible, and consistent online resources — stipulates that “sex” is, by definition, “the two main categories (male and female) into which humans and most other living things are divided on the basis of their reproductive functions”. Rather difficult to see how a potential reproductive function is likely to yield an actual zygote. And it is rather decidedly incoherent — at best — to argue that a given category can or should include both those who possess an actual attribute or trait and those who only merely potentially possess that attribute or trait. Should “teenager” encompass both those who are actually between 13 and 19 inclusive, and those who are just potentially so, who are somewhere between birth and 12 years old? Should it encompass — for the sake of completeness, and so as not to “exclude” or “dehumanize” anyone 🙄 — those who once WERE between 13 & 19 inclusive? Does not compute.

So, no: categories, to be of any use at all, particularly in scientific contexts, would seem to require that the defining characteristics shared by all members should be readily discernible, and easily quantified by objective criteria. And a “potential” reproductive role seems to fail on both accounts as it is so open-ended and subjective as to be virtually useless. A transwoman — compound word like “crayfish” which ain’t — might “reasonably” argue — as some have more or less already done — that “she” could “potentially” produce ova when/if she had ovaries transplanted — when pigs will fly — and thereby qualify — right now — as a “real” woman.

Consequently, there seems a great deal of justification to emphasize the centrality of, as MacLean puts it, the actual abilities “to produce sperm (male) or to produce ova (female)” as an essential part of the process of reproduction — particularly as the OED endorses those as essential attributes of those categories. And many feminist philosophers do seem ready to at least acknowledge the relevance of reproduction — Stock and Warnke in particular, the first only once in the context of “burden” and “inequality”, the second more extensively and broadly.

And relative to which, Ainsworth, in her Nature article and in the process of identifying and charting the various combinations of her own “clusters of categories” — i.e., chromosomes, gonads, and genitals (the same set of categories used in a case that, according to some “ideologically captured” editors over at Wikipedia, set the “legal precedent regarding the status of transgender women in the United Kingdom”) — nowhere stipulates or even suggests that gonads have any role at all in reproduction, much less that reproduction itself is central to the standard definitions of sex and of the sexes themselves. As MacLean suggested with her observation that Ainsworth failed to “first define her terms”, it is then maybe not surprising that Ainsworth — and those she echoes — should suggest that each of those subcategories are on par, that none are essential, and therefore that all of the many combinations she lists constitute a spectrum: “The idea of two sexes is simplistic. Biologists now think there is a wider spectrum than that.”

No doubt we can assert, somewhat arbitrarily or at least provisionally, that each category item in a cluster combination — for example, ovaries, vagina, and XY-chromosomes — is no more essential than any other — as, of course, Ainsworth, Fausto-Sterling, and Stock, in particular, have done. But IF one category of those on the table is, in fact, more essential than all others — as would seem the case with gonads since sperm and ova, particularly those that can be “delivered to the production floor”, are the sine qua non of reproduction — THEN, in that case, it seems we can justifiably claim to have a category (“sex”) of one subcategory (“functional gonads”) with as many combinations (2) as there are functional differences in the members (“ova”, “sperm”).

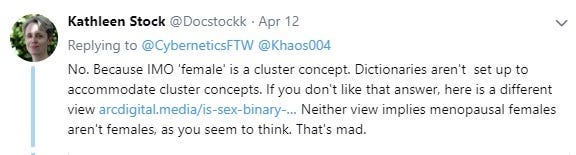

And it is then hard not to conclude, at least relative to the sex-as-a-spectrum [SAS] thesis, that many feminist philosophers & journalists — and many in the body politic who subscribe to their theses — seem motivated less by credible “adaptive or pragmatic purposes” than by “unexamined assumptions”, prior allegiances, or “motivated reasoning”. Or by outright vanity: “thy name is …”, although that is, of course, not unique to women, more of which later. But, for instance, many people — Stock and Stone in particular — appear deeply offended, or at least seriously “exercised”, by the consequences that logically follow from accepting non-cluster-category definitions —i.e., the axioms of the sex-as-binary thesis — for “sex” and for “female” in particular:

Not “mad”, Professor Stock; only what follows logically from accepting the premise that reproductive capability is an essential attribute of having a sex — which you seem to have done with your “the category of people associated with the burden of reproduction”, a connection that seems rather more than just an “association”. Although one might reasonably suggest that Stone herself, in effect, accepts or at least acknowledges that “that view does imply menopausees aren’t actual females”, even if she doesn’t show much interest in “entertaining” the idea for very long:

— — **** — —

However, to look at the other side of the coin, the so-called “scientific”, though more a folk-biology categorization — at least according to the definitions of Wright and Company — is also more or less equally problematic, and many of the problems it entails and motivates are based on and derive from some equally questionable if not self-serving premises, or interpretations thereof. While the sex-as-a-binary [SAB] categorization certainly seems to “hang together” better and have more utility than the competition for many very good reasons, many of its proponents, troops, and champions are equally reluctant to face the logical consequences of their own premises and “axioms”, and, as a result, engage in some championship-quality logical contortions to evade them. And while some few of the SAB camp are actually willing to have recourse to the standard definitions on which SAB is predicated — for example, biologist Jerry Coyne, although he may be using the subscription version of the OED which is apparently still stuck in the 14th century since they seem not to have heard of gametes — many others in that camp — like neuroscientist Debra Soh, evolutionary biologist Colin Wright, and even (!!11!!)

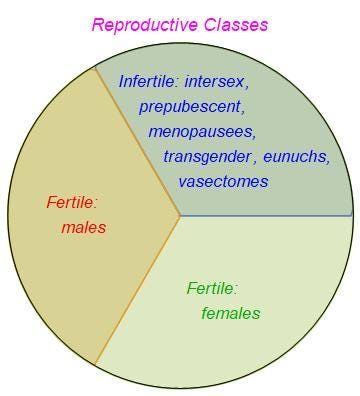

for examples — are decidedly and quite remarkably reluctant to face the consequential ramifications of the premises that are apparently near-and-dear to their hearts.And chief among those consequences of the standard definitions — i.e., those in which the actual ability to produce gametes is the sine qua non of “male” and “female” — is, as Stone suggested, that a far larger percentage of the population than was heretofore accepted as such lose their rights to claim membership in those quite “exalted” categories. Consequences which seem to “bite” a great many in both the SAS and SAB camps where it is most painful, i.e., in their fundamental senses of self, in their “identities”. Cue the outrage machines:

And for instances of that from the SAB camp — Stock & Stone in particular being exemplars from the SAS camp — we have the imperial edicts of both Soh and Wright who, while conceding that not everyone has a sex, are still reluctant to face what it means to have a sex in the first place, who also refuse to define their terms at the outset, and who therefore insist, without any justification, that the numbers are far lower than what logically follows from those definitions:

But if both Soh and Wright, and many others, are willing to concede that not everyone has a sex, as they have clearly done, then — having crossed that Rubicon, having already lost their “virginities” on that field of battle — one might reasonably ask, “If 1% don’t have a sex then why not 20% or 50%?” And one might also reasonably wonder if the category of “functional gonads” isn’t an essential subcategory of their concept and categorization of sex then have they not, in effect, thrown in their lot with Stock and Company by endorsing the “sex-as-a-spectrum” and category-cluster thesis? Heresy, apostasy, or hypocrisy? Or simply strange bedfellows caused by some motivated reasoning on both sides?

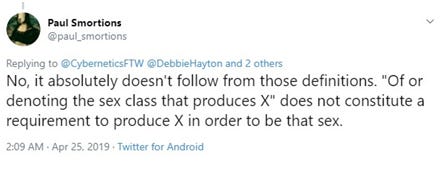

But apart from those champions of the SAS & SAB theses — who might reasonably be construed to be breathing the rarefied atmospheres afforded by living in various Ivory Towers — there are the many troops battling it out in the trenches who seem equally unclear on the concept of categories and the ramifications of the principles on which they rest. Which leads to a similar and equally problematic “misapprehension” as to subcategory sizes and membership. For some examples, many of those troops, mostly though not exclusively in the SAB camp, while acknowledging the applicability of the essential element of the standard definitions for “male” and “female” — i.e., “Of or denoting the sex that produces gametes” — attempt to argue that one can be “of the sex that produces gametes” while not actually being obliged to actually possess the ability to do so oneself:

And the common thread in those comments, and in many other similarly brave if not foolhardy assertions — one might almost think that it’s a political movement, that they’re all bots, that they’ve all gotten their marching orders from Putin … — is that, in their “minds”, the “sex class” is somehow a real entity that has some causal efficacy and agency of its own. And so, to set the stage based on our previous discussions about categories, IF we accept the fundamental premise — in our “grand” syllogism — that the sexes “male” and “female” are categories, AND then accept the secondary premise that to be a member of a category one has to possess the essential characteristics that define that category, AND then accept the tertiary premise that the ability to actually — NOT potentially — produce gametes in the process of reproduction is that essential characteristic THEN it seems to follow — more or less inexorably — that those who can’t so produce those gametes simply don’t qualify for sex category membership cards. Q.E.D.

But rather simply astounding that so many — including even some who should know better — apparently think that one can be a member of a category without actually being able or having to pay the membership dues. A serious puzzle as to how so many manage to reach that conclusion. And the most plausible explanation seems to be that they are guilty of the “sin”, the logical fallacy, of reification, of treating an abstraction — which a category manifestly is — “as if it were a concrete real event or physical entity”. So their “thought processes” — if we can dignify what they do by that term — seem to consist of treating the category name as if it were some sort of magic wand, the attachment of which to themselves triggers the spell or provides some sort of a “contact-high” from others actually in the category by virtue of having functional gonads. Tinker Bell or their fairy godmother goes ‘ting’, or twitches their nose and the pumpkin turns into a glass carriage and four — “back before midnight, you hear?” 🙄

Although to reiterate and emphasize for the sake of balance, there are more than a few in the “feminist philosopher” camp who likewise seem to have some rather wooish and self-serving ideas of what it means to be a member of a category. And a prime example of which is “Senior Lecturer in Political Philosophy” Holly Lawford-Smith’s Medium post, Is it possible to change sex? While she is commendably exhaustive, more or less, in addressing “four candidate theories of sex”, she also “snatches defeat from the jaws of victory” during the course of addressing, relative to one of those candidates, “the gametes theory”:

Whenever you chat to a biologist about what they understand ‘sex’ to be — and I have chatted to a few — they tend to talk about large and small gametes. Human sexual reproduction proceeds through the combination of sex cells of two different sizes (this is known as anisogamy): small gametes (sperm) and large gametes (ova). Males produce sperm, and females produce eggs. Almost no definitions that we give in philosophy have a single necessary condition, but sex is one of the few instances where such a definition works well.

Which is nice in itself, not least for championing the idea of defining sex based on a single category — gamete types — of which there are two, and only two, class (category) members. However she then similarly proceeds to go off the rails and into the weeds in discussing who gets to qualify as members and in which circumstances:

The best way to understand the ‘sperm or ova’ binary is that it’s true all going well. Of course, an individual man could end up with testicular cancer and have to have his testicles removed. Does that mean he’s no longer male? Of course not. He’s the kind of individual who, all going well, produces sperm. He’s not the kind of individual who, all going well, produces ova.

So, she, in effect, argues that there is some wooish, je ne sais quoi element that leaps into the fray, a philosophical Deus ex machina, that miraculously rescues such sadly “de-nutted” individuals from the shame and ignominy of no longer qualifying as members of that other exalted category, “males”. Apparently an equal-opportunity super-hero/heroine since she/he/it/they seem(s) to rescue Stock and Company from similarly tragic fates relative to the category “female”. But Lawford-Smith’s argument there rather looks like postulating that some *other* category — the “all going well” category? — has a significant role to play, elements of which are somehow magically capable of bestowing category membership absent the one that supposedly provided the “single necessary condition”.

In any case, that phenomenon and fallacy of reification seems rather more common than just in the transgender or feminism communities, even if it’s most problematic there, and seems substantially encapsulated or summarized by the Map–territory relation:

… describes the relationship between an object and a representation of that object, as in the relation between a geographical territory and a map of it. Polish-American scientist and philosopher Alfred Korzybski remarked that “the map is not the territory” and that “the word is not the thing”, encapsulating his view that an abstraction derived from something, or a reaction to it, is not the thing itself. Korzybski held that many people do confuse maps with territories, that is, confuse models of reality with reality itself. The relationship has also been expressed in other terms, such as Alan Watts’s “The menu is not the meal.”

And, as Korzybski notes and suggests, words themselves are just abstractions, just containers that we can more or less arbitrarily “fill” with things and attributes; they are just what we use to circumscribe, point to, or to denote — use as “a sign of” — various sets of certain supposedly real things. The anthropologist and naturalist Loren Eiseley in his The Immense Journey — a remarkably lyrical and profound set of essays on humanity’s evolution — argues that, in the dim recesses of history, we crossed a threshold when we humans became “a dream animal — living at least partially within a secret universe of [our] own creation and sharing that secret universe in [our] head with other, similar heads: symbolic communication had begun.”

And one might reasonably argue that the creation of those symbols, the naming of objects and categories [i.e., abstractions], is THE generative process and principle of that “secret universe”: in the beginning was The Word and the Word was god — so to speak. It is not without reason that taxonomy is frequently called the world’s oldest profession, at least metaphorically speaking.

But that “symbolic communication” becomes crippled if not impossible if we lose sight of the difference between the symbols themselves and what they refer to, if we can’t agree on what the symbols actually refer to, at least within some specified context, if we allow “hurt feelings” and Lysenkoist dogma to muddy the waters. For instance, a rather surprising number of transwomen, more or less boldly crossing the Rubicon, insist that they too are “adult human females”:

Although they are notably silent when asked what their definition is for “female”, and quickly abandon the field, unbloodied though frequently in a huff when asked if they, perchance, would agree it means “has concave mating surfaces” — as is the case with many plumbing and electrical connectors:

Now what we agree various symbols mean and refer to is somewhat arbitrary, although not entirely so: to be of any value in grappling with “reality”, the tools we use sort of have to have some degree of correspondence, a degree of conformance, with that reality. And agreement seems the virtual sine qua non of communication, if not of civilization itself. For example, it doesn’t apparently make much difference whether we drive on the left or the right-hand sides of the road — as long as we have some consensus, at least locally, as long as we agree which are the right and wrong sides, chaos being the result otherwise. But, in turn, an essential precursor of that agreement seems to be a common recognition of the “brute” facts — the reality, the actual “territory” — of any given matter or issue.

And in the case and context under discussion — primarily, what it means to have a sex, what it means to have a capacity for biological reproduction — those facts are that a rather large percentage of the population actually produce ova that can be used in the process of reproduction, and that a more or less equally large percentage actually produce sperm that can be used in that same process, and that a more or less equally large percentage actually produce neither. Now we can, if we so desire, create some brand new words to describe, to denote those brand new categories which may be of some utility, particularly since the words conventionally used have become so freighted with emotion, with “hurt feelings”, with egregious and odious dogma, and with so much highly questionable “science” as to be virtually useless, particularly for adjudicating any claims from men — i.e., adult human males (testicle-havers) — to access women’s sports, prisons, toilets, and change rooms.

So, in consequence and relative to which, one might tentatively suggest a couple of hyphenated words — based on Latin for some extra pizzazz — to cover all of those bases, to create a set of exhaustive categories, to name them for some as yet unspecified “adaptive or pragmatic purpose”. To wit: producit-ova (produces ova); facit-sperma (produces sperm); and, for the sake of completeness and to remove any possible wiggle-room, neque-sperma-neque-ova (produces neither sperm nor ova). In addition to which — since it is more or less a given that the process of sex is, by definition and by common understanding, fundamental to and in itself denoting the process of biological reproduction — we might also assert that those first two categories are or can be called the two sexes by virtue of being the only categories of those able to take part in reproduction.

Now we have, of course, and in all likelihood, recapitulated the process by which the conventional definitions for the terms “male” and “female” were created in the first place. But we have also disconnected them from all of the emotional and ideological baggage that the conventional ones have acquired and have become burdened with, mostly of late, including the perception and claim that they are “immutable”, that they are anything other than as entirely transitory and ephemeral as the category “teenager”. However, while we might then reasonably use them for our putative “pragmatic purposes”, we might first consider that if they were to then acquire, as they would likely do, much in the way of the currency and cachet that the current definitions have acquired — particularly “female” — then it might not be long before many transwomen would be claiming they too were “producit-ova”, and expecting — nay, demanding — to be treated the same way, particularly since a rather large number of transactivists seem less motivated by logic and reason than by outright envy:

Now, in consequence, there is maybe, as Stock argued, some justification, in the context of transgender “sex changes” — a biological impossibility — for “knowingly engaging with and generating fictions” as “a crucial part of sensitive social interaction, and of sparing the feelings of others”. However, for all her genuflecting to “retaining a much-needed grip on reality”, it is still hard not to see her wish to “grant those suffering from severe dysphoria the option of a legal sex-change” as a repudiation of that “grip” — and as a case of ignoring the fact that such legal fictions become the thin edge of the wedge to let more problematic issues in the door. As has already been proven to be the case in far too many situations, and which have turned out to be very sticky wickets, indeed.

But relative to which, it is maybe worth noting that Edward Albee — author of the play, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf which turns on the difference between reality and illusion — suggested a broader theme of “who’s afraid of living life without false illusions?” A question that might be said to challenge us all — the sword of Damocles hanging over all our heads; “pray tell, by what thread does thy life hang?”

Apropos of which, of those threads, I’m reminded of a old Slate article — “The Trans Women Who Say That Trans Women Aren’t Women” — by Michelle Goldberg who had interviewed transwoman “Helen Highwater”:

Yet [Highwater] has come to reject the idea that she is truly female or that she ever will be. Though “trans women are women” has become a trans rights rallying cry, Highwater writes, it primes trans women for failure, disappointment, and cognitive dissonance. She calls it a “vicious lie.”

“vicious lie”, indeed. Helluva thing that so many people are being parties to such lies, are “accessories before and after the fact” of that crime. Which dysphoric and autistic children bear the brunt of.

But it can’t be considered conducive to much in the way of social, moral, or intellectual progress to lose sight of the profound and far-reaching differences between the sexes, to be trying to sweep those differences under the carpet. As T.E. Huxley put it:

For those who look upon ignorance as one of the chief sources of evil; and hold veracity, not merely in act, but in thought, to be the one condition of true progress, whether moral or intellectual, it is clear that the biblical idol must go the way of all other idols. Of infallibility, in all shapes, lay or clerical, it is needful to iterate with more than Catonic pertinacity, Delenda est.

While he was, of course, focused primarily on religious fundamentalism, although his shots at claims to infallibility clearly cover much more ground than just that, his call to “veracity not merely in act, but in thought” clearly has a great deal of relevance to the whole dog’s breakfast and bedlam of transgenderism. And to the competing “theories” of sex that motivate many on all of the different sides of the issue.

And it should be manifestly obvious from the foregoing that we have a serious disconnect — exhibited on many sides, in many camps, and by many of the players on the field: troops and champions, “saints and sinners” — between the facts on the ground relative to our reproductive capabilities, and the theories — and the categories that undergird them — that attempt to describe and encapsulate those facts. IF we accept that to have a sex is to have a reproductive capability — as most people seem to do, if reluctantly, evasively, or under some duress — THEN it should be abundantly clear that all of us — at various stages in our lives — didn’t, don’t, or won’t actually have a sex, and that “sex” itself is a rather decidedly transitory category.

And, relative to which, one might note, somewhat in passing, the number of transactivists and even many of the “intersex” who have rather strenuously objected to being shoehorned into the categories “male” and “female”, and who have expressed a preference for “none” under the rubric of “sex”. Given the resentment that many women have expressed for being similarly shoehorned into the category “cis”, one might think they at least would have some sympathy for those objections. Making more out of membership in particular categories — mere abstractions — than is justified, and transitory ones at that, doesn’t seem all that conducive to “peace, order, and good government”.

But that then raises a number of other problematic aspects, although they tend to be quite a bit more tractable than having to adjudicate between competing “subjective narratives”, between idiosyncratic “fictions”, and inconsistent “theories”. And foremost among those aspects would seem to be the question, if “sex” is so transitory then what do we put on our birth certificates and driver’s licenses? And the simplest answer would seem to be to use the category of karyotype. While that attribute is generally not readily or easily discernible, our genitalia at birth provide proxies that can be used until it becomes evident that there are discrepancies — a proxy being “a variable that serves in place of an unobservable or immeasurable [one]” which is what is already the case with our sexes. We would, on the basis of our birth genitalia, infer a most likely karyotype, or perform genetic tests if those were ambiguous. In addition, the use of karyotypes would likely resolve the fractious “debate” over Women’s Sports: no X-Y need apply.

In addition, on the view that the sex categories are transitory, one might conjecture that data acquired by characterizing populations — heights, behavioral attributes, and susceptibilities to various drugs, all of which show notable differences in means by sex — are somewhat suspect. While this issue is unlikely to directly affect the day-to-day life of the public, using karyotype — which clearly IS a spectrum — in scientific studies as markers or as independent variables is likely to be far more accurate, useful, and safe:

But, to conclude, creating and promoting categories based on political or emotional criteria seems to muddy the waters unnecessarily, and causes far more animosity and grief than is justified. All of which might be forestalled, or greatly reduced, if we were to exhibit and promote a bit more intellectual honesty, a bit more “veracity”, in how we define and use those categories.

I just feel, you know, that out there in the woods the birds and the bees are laughing.