Rerum cognoscere causas

Mechanisms in Science: things learned at my mother's knee and other low joints

That Latin phrase is the motto for the London School of Economics — and which was on a sweat-shirt that my mother — gawd rest her soul — gave me some 30 years ago:

Though the exact reason for the gift, sadly lost in the mists of time, is somewhat unfathomable since neither of us ever went to the LSE. But, according to a translation by Dryden (1697) of Virgil (30 BC), it means:

"Happy the Man, who, studying Nature's Laws, Thro' known Effects can trace the secret Cause"

Although the concept, arguably the foundation for pretty much all of civilization, goes back much further, at least to the time of Proverbs (4:7), possibly the second-millennium BCE:

Wisdom is the principal thing; therefore get wisdom: and with all thy getting get understanding.

So — understanding how things work is rather important, not least because the survival of our technological civilization probably depends on it, and on many fields of battle. As something of a case in point and of more than passing relevance, Steven Pinker, in his The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature, talked of the “leaky pipeline”, of how “women make up less than 20 percent of the workforce in science, engineering, and technology development, and only 9 percent of the workforce in engineering” — and despite them being “about half of the students majoring in many fields of science.” No doubt part of that is simply a matter of interest — as he quotes “social scientist Patti Hausman” saying, rather amusingly, she and many other women are simply not terribly “interested in learning how my dishwasher works." Maybe, in large part, because their “biological clocks” run at a very different tempo from those of men.

However, that attitude, that “incuriousness” — at best — about “Nature’s Law’s” problematically plays out in many other areas, notably — as the (female) authors of Professing Feminism once suggested — in the “virulently anti-science, anti-intellectual sentiment driving many of the professors, staff and students” in various Women Studies programs all across the land. As Helen Dale — of Not On Your Team, But Always Fair fame — once put it in a review of Louise Perry’s The Case Against The Sexual Revolution, feminists, in particular, need to “take biology seriously”. Somewhat surprising that many don’t since they obviously tend to carry heavier burdens in the reproduction department — which has many far-reaching consequences, indeed.

Consequently, as a way of bringing “nature’s laws” to bear on some of the “burning” questions of the day — notably, “What is a woman?” — and particularly where they may conflict with “man’s laws” and/or “gawd’s laws” — Genesis 1:27 in particular —it will be useful to review some of the philosophical principles and insights that motivate the standard biological definitions for the sexes. And the text for this (or last) Sunday’s sermon will largely be the Mechanisms in Science article from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (SEP). To start with, consider their opening salvo and something of a synopsis of their theme for reference:

Around the turn of the twenty-first century, what has come to be called the new mechanical philosophy (or, for brevity, the new mechanism) emerged as a framework for thinking about the philosophical assumptions underlying many areas of science, especially in sciences such as biology, neuroscience, and psychology. ….

To many such scholars raised in this post-logical empiricist milieu, it appeared that much of the practice of contemporary science (both in the laboratory and in print) was driven by the search for mechanisms, that many of the grand achievements in the history of science were discoveries of mechanisms, and that more traditional philosophy of science, for whatever reason, had failed to appreciate this central feature of the scientific worldview. .... Machamer, Darden and Craver’s “Thinking about Mechanisms” (... MDC) drew these strands together and became for many the lightening rod of the new mechanist perspective. MDC suggested that the philosophy of biology, and perhaps the philosophy of science more generally, should be restructured around the fundamental idea that many scientists organize their work around the search for mechanisms.

Fairly thorough and quite fascinating article, and they cover a lot of ground — I’ve only managed to chew through some half of it, and much of that is not yet fully digested. However, most of it is fairly well organized and it’s possible to see important aspects and outlines that may help to adjudicate competing claims about various definitions for the sexes. Although spectrumist views are generally non-starters — notwithstanding claims of erstwhile reputable biological journals like Cell to the contrary. But too many ostensible biologists (e.g.,

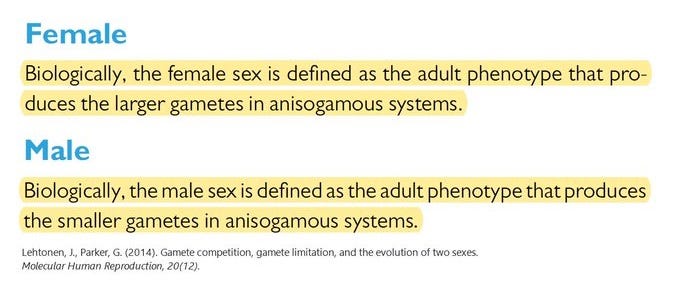

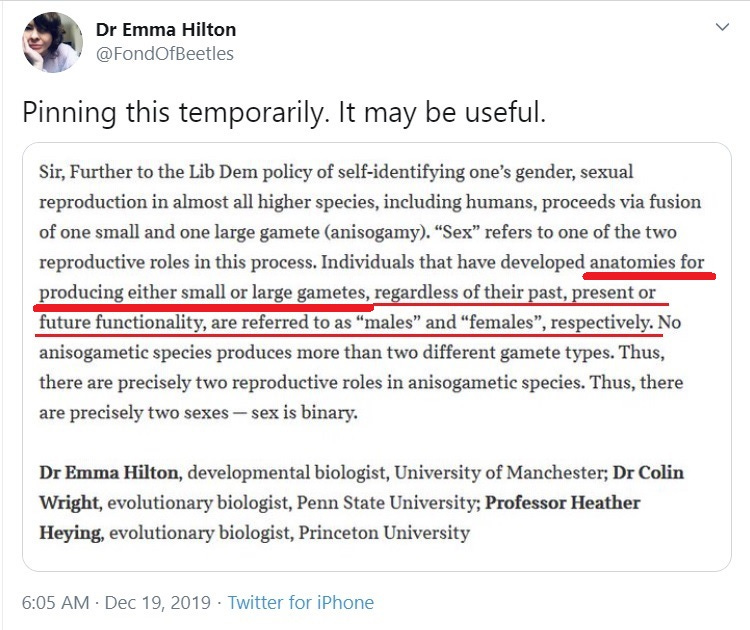

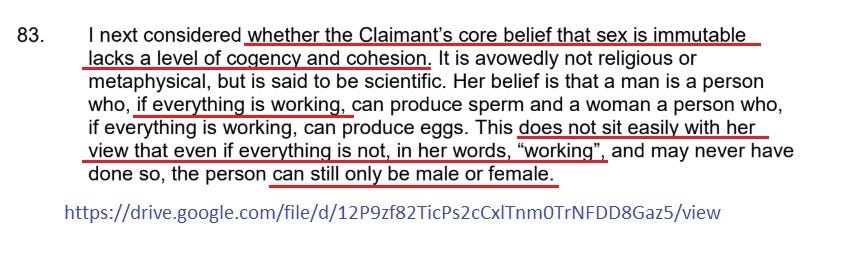

) and philosophers (e.g., Alex Byrne, maybe too beholden to his “partner in crime”, ) are peddling definitions that are hardly better that folk-biology or even the Kindergarten Cop versions: “boys (males) have penises and girls (females) have vaginas”. Maybe useful for controlling access to various toilets for the kiddies but not much else.But a big part of the problem is that there are two very different and quite incompatible ways of looking at the sexes: mainstream biology defines the sexes as transitory properties based on the presence of functional gonads — and of either of two types — whereas various folk-biologists, feminists, and their white knights totally disconnect membership in those categories from any necessity to be “reproductively competent”. Or often see the sexes as no more than participation trophies or identities based on something not far removed from “immutable essences”:

The first from the Glossary of an article in the Oxford Journal of Molecular Human Reproduction, the second from

and “another exemplary peer-reviewed biological journal” (🙄 —the letter section of the UK Times), and the fourth from Maya Forstater’s court case several years ago. So no wonder that the kids are confused — if not led astray, often for fun or profit.Though it’s a bit “disconcerting” to see Hilton and Wright — in that tweet of hers — peddling that quite unscientific folk-biology when they subsequently, in an article in the Wall Street Journal (archive link), quite reasonably railed against “The Dangerous Denial of Sex”. Politics and strange bedfellows …

But an oldish essay in Psychology Today by Robert King — Terf Wars: What Is Biological Sex? — speaks, rather sternly, to those “essences” and provides a useful lead-in to SEP’s discussion of mechanisms in general [my emphasis]:

However, I would like to offer one perspective on the issue of who is, or is not, essentially a man, or essentially a woman.

No one.

Both sides are wrong. …. The reason that they are wrong: …. No one has the essence of maleness or femaleness, for one simple reason: Since the 17th century, what science has been showing, in every single field, is that the folk notion of an “essence” is not reflected in reality. There are no essences in nature. For the last three hundred years or so, the advance of science has been in lockstep with the insight that is what really exists are processes, not essences.

Though it might be emphasized that he is apparently using “man” and “woman” as sexes — i.e., as “adult human males and females” — and not as genders, an entirely different kettle of fish.

But of particular note also is his broaching and summarization of the idea of functionalism which the SEP article elaborates on in some detail:

Being is, as being does

We have a name for this in science, “functionalism.” But, don’t worry about the technicalities or the jargon. The essence (see what I did there?) of functionalism is this: Something is, is what it does. Or, to put it another way, the scientific revolution largely replaced nouns, with verbs.

Hence — “produces gametes”, present tense. And that process, and the mechanisms that are part and parcel of it, are absolutely ubiquitous across literally millions of anisogamous species. Why many have, quite reasonably, argued that that property, or sex generally, constitutes a “natural kind”, the description and elucidation of which more or less characterizes science in general. Although, en passant, one might emphasize — somewhat tentatively, given that many (e.g.,

& ) are “offended” by the observation or the conclusion — that not all members of those species are always producing one type of gamete or the other — embryos for one example, and prepubescent human children for another. Yet we still consider the latter as human beings despite that “failing” — even if one might suggest that people generally don’t qualify as such much before being thirty years old.In any case, because of that “ubiquity” — not to mention that property’s centrality to pretty much all of biology — there is some justification for delving into the different types of mechanisms, the boundaries to them, and how those perspectives inform and justify those definitions. However, while SEP does go into some fascinating depth in describing the salient features of mechanisms, they also tend to go off into the weeds with all sorts of qualifications and sources to justify the many different variations. Consequently, it will be useful to focus on the basics, and on a simplified example thereof, particularly since their illustration of the relevant principles is somewhat too abstract, at least to begin with. Their summation of the “essence” of mechanisms [my emphasis]:

Each of these characterizations contains four basic features: (1) a phenomenon, (2) parts, (3) causings, and (4) organization. We consider each of these in detail below.

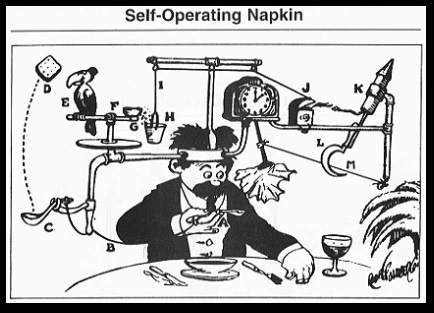

Apropos of which and of particular note from the SEP article is their assertion that “The phenomenon is the behavior of the mechanism as a whole”, and that the “organization of all of its components captures the sense in which mechanism is composed of separable, interacting parts.” Which is nicely illustrated by various and typically quite amusing “Rube Goldberg Machines (Mechanisms)” (RGM), and, in particular, the classic “Self-Operating Napkin” courtesy of “Professor Butts”. Whot a concept, bound to take The Shopping Channel by storm:

But the “phenomenon” in question here is the regular wiping of the Professor’s chin and beard because the napkin is attached to the pendulum of the mechanical clock (N?). But the complete “organization” of the mechanism consists of further parts A (“soup spoon”) through interacting parts B, C, … and L (“sickle”) to the restraining string (M) — the cutting of which by (L) allows the clock pendulum to swing back and forth wiping the professor’s chin. Magic! The Man Behind the Curtain! Dorothy, we’re no longer in Kansas — no “essences” involved. Which is kind of the problem with processes in general since many of the steps involved, many of the “causings” happen “underneath the hood”, or behind the curtain. It is not for nothing that sci-fi author Arthur C. Clarke once observed that “a sufficiently developed technology is indistinguishable from magic”.

But there are several other things of particular note in the foregoing, and of some relevance to the definitions for the sexes, one of which is that pretty much all of the parts — A through N — of that “Self-Operating Napkin” are, in themselves, mechanisms as well. For one example, the bird E flying off from pedestal F tips seeds G into pail H. And the clock itself is a mechanism in its own right, and arguably a more fundamental one. Thus, there are a whole series of subsidiary causes and effects leading to the primary effect, to the phenomenon in question, i.e., the back-and-forth motion of a napkin on the pendulum.

However, it should also be noted that the whole process from the Professor lifting the spoon (A) to his mouth to the napkin (N) swinging back and forth some dozens of times only happens once, whereas, as indicated, the swinging of the napkin happens many times and with some degree of regularity. Which is apparently why SEP more or less emphasizes at least those two types of mechanisms — one size does not fit all:

Mechanisms are entities and activities organized such that they are productive of regular changes from start or set-up to finish or termination conditions” ….

Must the relationship between the mechanism and the phenomenon be regular? This is an area of active discussion. MDC stipulate that mechanisms are regular in that they work “always or for the most part in the same ways under the same conditions”. Some have understood this (incorrectly in our view) as asserting that there are no mechanisms that work only once, or that a mechanism must work significantly more than once in order to count as a mechanism.

So — several types of mechanisms: those which work either once, irregularly, or regularly. However, because there are often many different steps or “causings” that contribute to the “phenomena” in question — as in the self-operating napkin — it is often, apparently and particularly in biology, more useful to focus on the regular steps involved in particular cycles. And to name them accordingly. For examples, there are the respiratory, blood circulation, citrus acid, and urea cycles — we, biologists more particularly, give names to those cycles because they often have far-reaching consequences in the survival and propagation of many cells, and the organisms which are built from them.

So there you have it ladies — and gentlemen: how your dishwasher works.

But it is not just biology where cycles play more than just a definitive role. For instance, it is part and parcel of the mathematics of group theory, although much of that is — also, I’m sad to say — well outside of my salary range. But some of the salient elements are more or less easily illustrated and comprehended. For example, the Rubik’s Cube puzzle is a particularly illuminating case:

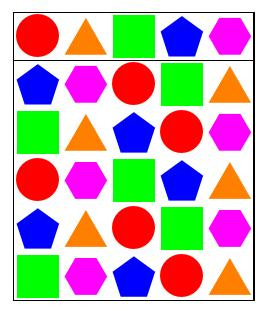

Somewhat simpler is the following group which should underline both the concept of cycles, and the “parts” and “causings” that SEP refers to:

In the above graphic there are six separate rows of five coloured geometric shapes in each row. And each of the rows is transformed into the row below it — or to the first row in the case of the last row — by the application of a particular set of rules. Those “rules” say to move the first item in the each of the given rows to the third position in the next (or first) row, the second to the fifth position, the third to the fourth, the fourth to the first, and the fifth to the second. So with that particular set of rules — the “group operation” in the lingo of group theory — the cycle repeats after six steps. Though it might be noted that there are two sub-cycles, columns 1, 3, & 4, and columns 2, & 5.

Consequently, we might say that the phenomenon is the cycle itself, the parts are the five shapes, the “causings” are the rules, and the organization is the five columns and six rows.

But something else from SEP on those different types that bears some emphasis (section 2.1.1) as it is particularly relevant to the biological definitions:

New mechanists speak variously of the mechanism as producing, underlying, or maintaining the phenomenon (Craver and Darden 2013). The language of production is best applied to mechanisms conceived as a causal sequence terminating in some end-product: as when a virus produces symptoms via a disease mechanism or an enzyme phosphorylates a substrate.

Similarly with the regular production of gametes which are the phenomena that need explanation and understanding. Those are the penultimate steps in the whole process of reproduction which are essential to the survival, and evolution, of many species. And apparently why reputable biologists have used “male” and “female” to label those organisms which are currently, and regularly producing either of two types of gametes. However folk-biologists want to define the terms, however much many want to make them into fashion accessories or “immutable identities” based on some “mythic essences” — as UK “philosopher” Jane Clare Jones once amusingly, and cogently, put it — it is the presence of regular cycles of the production of sperm and ova that are the phenomena that undergird much of biology — theory and practice.

It is often moot what are the many factors that lead to the presence of a given cycle — whether it’s an automatic chin wiping mechanism or the production of gametes. For example, many species have very different sets of chromosomes from the Xs and Ys that characterize humans and other mammals yet they all still have males and females, they still produce large or small gametes. And in many species, alligators for example, both males and females apparently have the same sets of chromosomes — sex is determined by the temperature at which the fertilized egg is incubated. But regardless of those many factors, many different sets lead to the same phenomenon: the regular production of either large or small gametes. Definitive and with far-reaching consequences, both biologically and sociologically, the cycles themselves or their precursors.

However, another major part of the problem is that many people don’t have a clue about the nitty-gritties of reproduction — maybe not unreasonably, at least in some cases, as “doing what comes naturally” generally doesn’t require much understanding of those intricacies. Though when the general ignorance of such details precludes equitable resolution to various social problems, if not contributes to them, then one might reasonably say, “Houston, we have a problem”.

A problem which is somewhat intractable because the mechanisms involved — gametogenesis in general, spermatogenesis in males, and oogenesis in females — are rather intricate indeed, almost unfathomable in fact. Which leads to some “unfortunate” and problematic “cognitive distortions” — a salient one of which is the view that human XXers are born with all of the ova they will ever need, all preformed and ready to rock and roll right out of the chute — which is most certainly not the case. In fact, for both XXers and XYers the “assembly line” isn’t “on line” and cranking out product — on a regular basis — until the onset of puberty. Until then we are all, at least by standard biological definitions, sexless. Which, surprisingly or not, doesn’t sit well with many people, UK “philosopher”

for example:So given that complexity it is maybe of some use to consider, below, something of a stylized assembly line — Henry Ford would be proud of me. (Once the video is started there are options to speed up or slow down the display which shows three production cycles):

What is shown is a platform that moves across the production floor, and on which a series of components are placed — and then bolted and wired together by a dedicated team working tirelessly behind the scenes. Once the platform reaches the end of the assembly line, the “gizmo” under construction — whether it’s an ovum, spermatozoa, car, or dishwasher — is complete and is moved off to the storage yard or immediately on to perform the function it was “designed” to do. Though one might emphasize that what is on the platform does not at all qualify as an ovum, sperm cell, car, or dishwasher until the last stage, until the very last component is added and integrated into the rest of them.

But all of that is, more or less, exactly what happens in gametogenesis, although the steps, components, and “cycle times” for the production of ova are very different from those for the production of spermatozoa. For one thing, human females only crank out one or two ova a month, whereas human males crank out some 100 million spermatozoa every day. Largely because there are very significant differences in the size, structure, and complexity of ova versus spermatozoa — for example, each ovum is about 100,000 times the volume of each sperm cell. So, the difference between building one or two Ferraris a month versus thousands of Volkswagen beetles — so to speak.

But the foregoing should emphasize and illustrate the process, the mechanisms by which gametes are produced. In particular, one might suggest that it could have taken several years to build the “manufacturing plant” shown in the video, and to train the workers, to develop the supply chains that provide all of the subcomponents. But none of those elements are actually or directly part of the manufacturing cycles that produce some gizmo at the end of it.

Likewise with gametes — some 10 to 15 years from “start-up” to the point where the plants are on-line and cranking out product on a more or less regular basis. And they may well be “shut-down”, for one reason another, and well before the end of the lifetime of the owning “company”. But all of foregoing is largely why the biological definitions for the sexes make the regular production of gametes into the sine qua non for sex category membership.

Biology in general, human biology in particular, encompasses some remarkably complex though fascinating processes, cycles, and mechanisms. But even apart from the biology itself and its bearing on medical science, it also has a great deal of relevance to many significant social policies and thorny social problems. Maybe we should be making more of an effort to understand and utilize the principles and insights that motivate and undergird much of the whole edifice?

As E.O. Wilson was quoted saying in The Splendid Feast of Reason (highly recommended):

To chart our destiny means that we must shift from automatic control based on our biological properties to precise steering based on biological knowledge.

Sex is indeed supposed to have a very narrow definition, and I feel like you and I are in a very tiny minority on resisting its expansion.

This article begs the question: How does a definition of a man as someone who is currently successfully producing small gametes, and of a woman as someone who is currently in a cycle of producing large gamete(s), successfully allow us to determine who gets to use which bathroom, play in which sports league, live in which prison, etc.? And do these definitions help determine whether it is a good idea to push synthetic cross-sex hormones and surgeries to remove healthy body parts (and/or create faux parts that don't look, feel or perform like the real thing, and stitch them onto otherwise health bodies), particularly on very young and vulnerable individuals, for the simple reason that they seem to want this?

Since this seems to be the point you are making (ie. if we want to create good social policy, we must understand the scientific definitions of "male" and "female" and "man" and "woman" and "boy" and "girl" - not a bad concept), it would be nice to have a part 2 of this article in which you show how the definitions you propose are useful for this goal.

I still don't see the present tense aspect as being part of the definition at all. In fact, the "male" and "female" definitions provided early on in the article indicate male and female as the one "that produces" small or large gametes, respectively. Nothing in that phrase indicates present tense, as the one "that produces" something could produce that thing at any point in its existence, as long as nobody outside of that class produces that thing. In other words, for example, a female is the one that produces large gametes, from puberty through menopause, not before or after that time.

Anyway, I liked the video of the car being made in the factory and I especially liked the napkin mechanism, although I'm not sure they gave me any insight into the answer to the definitions of "male" and "female." Overall, it was a thought-provoking article, and fun to read. My favorite part: the gift your mom gave you. :)