What on earth, my faithful readers might reasonably ask, do the above four fictional characters have to do with the burning question of the day, the one that has confounded philanderers, philosophers, and politicians since time immemorial? At least since Adam took a (de)ribbing from Jehovah — so to speak.

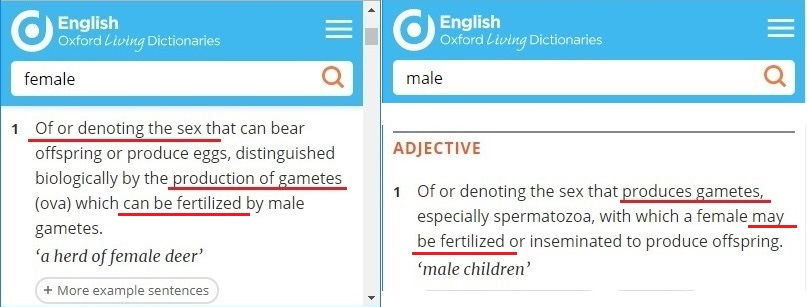

But a very good question, the answer to which, and to the maybe broader issue of transgenderism, may lie in some pervasive and fundamental confusions over the nature, definition, and use of categories. A question which will bear some urgent, necessary, and essential analysis and discussion. And a major source of that confusion seems to be whether the sexes are to be seen as simple categories or as “immutable identities” based on some “mythic essences”. For instance, Google/Oxford-Dictionaries clearly defines the sexes as categories based on reproductive functions, even if they’re a bit vague on the specifics, although those for “male” and “female” are substantially more “definitive”:

And, on the other hand, the judge in the Maya Forstater case accurately, if somewhat sarcastically, summarized her position as a “core belief that sex is immutable”:

Presumably that “immutability” is based on some “magic essence” that’s present regardless of whether “everything is working” or not. Which raises the question as to why, for example, transwomen can’t claim to have the magic essence of “female” since it seems unquantifiable. But that insistence on “immutability” is rather typical, particularly among various “sects” of feminism — here and here for examples.

However, as Wikipedia puts it, “Essentialism has been controversial from its beginning” — bit of a misstep on the part of Plato and company. There are some serious problems with that whole concept, although most of those are largely irrelevant to the basic applications we will be discussing here, at least in this post. But along the same line, Robert King in an essay at Psychology Today — Terf Wars: What is Biological Sex? — quite reasonably argues that “there are no essences [mythic or otherwise] in nature”, and that “the advance of science has been in lockstep with the insight that what really exists are processes, not essences.” For example, the standard biological definitions for the sexes — linked-to above, and endorsed by Google/Oxford-Dictionaries — are based on the processes of producing either of two types of gametes as the defining and essential properties:

More of which in later posts relative to the ubiquitous and “problematic” conflicts over defining the sexes as a binary or as individual spectra.

However, given those rather acrimonious and enervating conflicts, it seems worthwhile to review some of the basic principles that undergird categories and categorization, and to illustrate both their application, and misapplication to some tangible and more abstract examples, including to the question of the day.

Magic of Categorization:

Categorization is basically what we all do, all the time — whether it’s the mundane categorizing of edible “stuff” as poisonous or nutritious, putting tools and writing instruments into their proper containers, or putting millions of species into some sort of hierarchy of categories — the science of taxonomy. Categorization is largely essential, not just to daily life, but to the whole edifice of civilization, and to the sciences on which much of it rests — even if somewhat precariously given the depredations of gender ideology. As Steven Pinker put it in his How the Mind Works:

“An intelligent being cannot treat every object it sees as a unique entity unlike anything else in the universe. It has to put objects in categories so that it may apply its hard-won knowledge about similar objects, encountered in the past, to the object at hand.” [pg. 12]

However, there are a number of serious pitfalls that are too easy to fall into without some careful attention to a few readily understandable principles and basic definitions. All of which might be grasped by considering a couple of tangible examples.

To begin with, categories are basically containers that we put “things” into because they all have certain properties in common that justify their inclusion in those containers. One justification being that the things are easier to carry around, particularly if there’s a handle on the container. But for a tangible example, consider an analogous case of a bunch of tools — pink handled for the ladies — which we put into a classy antique tool-box (Etsy, a bargain at only $385.00 …):

But the tool-box itself is analogous to categories in general while the tools themselves are analogous to what are called the members of the category. Another example is that of putting a bunch of coloured pens and pencils into a pencil-case. But the principle and its applications are ubiquitous and foundational: members of a category, and the “enclosing” category itself.

However, there is an important difference between containers like tool-boxes and pencil-cases, on the one hand, and categories on the other hand. Basically, the former are tangible; they have weight and volume — at least on the outside and enclosing edges. But categories are generally abstractions; they only “exist” in our minds, brains, and conversation. Consider the definition from Oxford Dictionary — which is what Google uses, and what you get when you do a Google search for “category definition”:

Note in particular the “regarded”, that is, perceived by us. We see that certain “things” have certain properties in common so we draw mental boxes — containers — around them and then give labels to the containers we have created. “Social construction” writ large — one for the postmodernists. However, there are a few tricky steps involved in that process that are far too easy to stumble over, but a more tangible and a somewhat non-controversial example may illustrate both the processes and the pitfalls.

A category for all seasons, for Jane, Dick, Nemo & Dino:

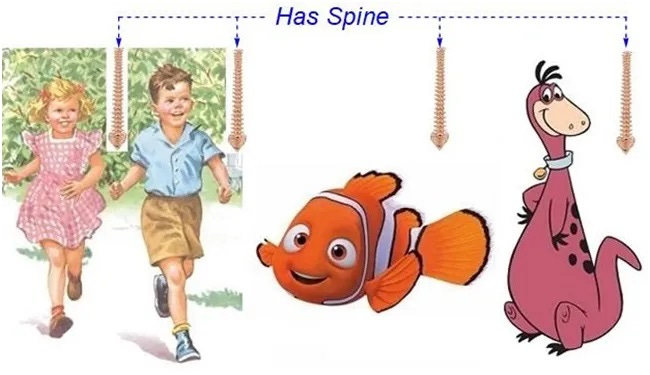

To begin with, consider once again the four critters that we started our journey with. What might be the common element in all of them? All are fictional characters of course, although they may share many other traits — being part of childhood developmental processes, for example. However, at least for the sake of exposition, we will, somewhat arbitrarily “pick out” a particular trait that each critter “shares” with the others, i.e., they each have a spine:

But the above more or less just emphasizes an important aspect of categorization, and of the naming of categories in general: we pick out particular traits because, paraphrasing Pinker, we can apply what we learn about one object in the category to other members of it. In addition to which, the larger the group that has a trait that differs substantially from those of other groups, the more useful the category becomes — sort of like “male” and “female”. But basically categories permit and undergird the argument from analogy — not a perfect tool, but substantially better than “treating every object we see as a unique entity”.

However, it might be emphasized that it is, of course, not a case of them, in effect or actually “sharing” the same spine: they each have different spines from a “box” of them, from the category “spines”. For example, Dick and Jane, like most mammals, have spines composed of 33 vertebrae, although there are probably some significant differences because they are nominally of different sexes. But Nemo and Dino have substantially different numbers — Nemo, like most fish, may have 50 or more, while Dino, like most dinosaurs may have 75 or more. However, they’re all spines because they each have some traits in common, primarily a variable number of vertebrae of different sizes that enclose and protect a spinal cord, a nerve bundle running the length of the organism.

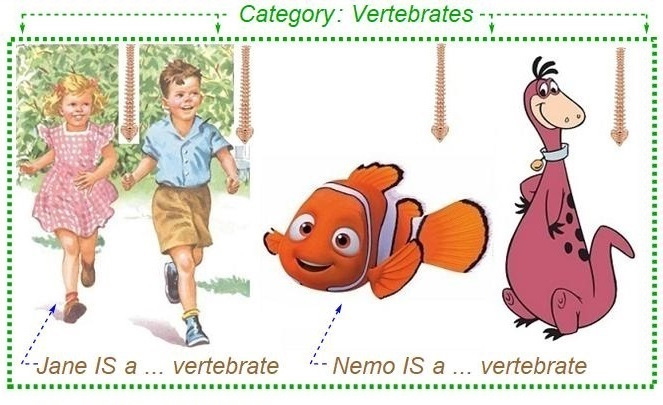

But now that we have identified a common property — typically called universals in philo-speak — we can now draw a box around our category to enclose its members, and then give a name to that box and its members. For example, just to pull something out of thin air, say “vertebrates”:

Although it bears emphasizing that the name given is somewhat arbitrary — a rose is a rose is a rose. And likewise that the category name is “vertebrate” while its members are vertebrates. But it’s largely immaterial what we name the box we’ve drawn around those organisms, as long as we agree that it encloses organisms that have a spine; the important thing is the property shared, not the name given to the container. The name is more or less equivalent to just the handle on our antique tool box — simply an easy way of moving “containers” around in our workshops or our minds.

But that particular box itself is, once again, a specific example of a category, and the word "vertebrate" is the label conventionally used for that particular box — the word itself is something that "denotes" or is a sign of a particular "sharing", i.e., "has a spine". From which it follows that each of those "animals" is then said to be "a member of the category vertebrate" which is conventionally shortened — a case of ellipsis — into saying that, for examples, "Jane IS a [member of the category] vertebrate", or "Nemo IS a [member of the category] vertebrate":

Although that ellipsis is something of a trap for the unwary since the use of “is” easily leads to the confusion that memberships in categories are “immutable” identities. We wouldn’t for example, argue that the statement, “Sally is a teenager” means that “teenager is immutable”, or that there’s some “mythic essence” to “teenager” that might justify someone of 35 “self-identifying” as a teenager. Yet that is precisely what is happening when it comes to “woman” and “female”.

But "vertebrate" isn't a thing in itself, the word is just an intangible membership card in that category, the membership dues for which is actually having a spine: it is that possession of a spine which is the "necessary and sufficient condition" to qualify for membership in the category. None of those critters is any heavier as a result of being put in that “box”; they aren’t burdened, physically at least, by having to carry around some tangible, weighty, and onerous thing called “vertebrate”; we couldn’t possibly do an autopsy on any one of them and locate, much less measure and weigh the “thing” called “vertebrate”. The category name “vertebrate” is something that “exists” only in the minds of those individuals who perceive that those four critters — and millions of others — share the property of “has a spine”. Likewise with other categories — like “woman”, “female”, and “teenager”.

Cutting to the chase: What is a woman?

So — my faithful readers might now reasonably ask — how do those principles of categorization help us to answer the question, “what is a woman?” Well, as a statement of first principles, “woman” is commonly defined and accepted as “adult human female” — at least outside of the benighted British Labour Party — while, as indicated above, “male” and “female” are, by definition, categories that are more or less defined by the presence of “reproductive function”. Although there are a few devils in the details of the definitions for the sexes themselves — and that largely because various so-called biologists, medical doctors, philosophers and skeptics are still trying, rather desperately, to turn the sexes into spectra. For which reason, a fuller discussion of the problems and ramifications of that particular aspect of the problem will have to wait for a later post.

However, even if we accept that the definition for “female”, in particular, is something of a black box or a “work-in-progress” — a known unknown — we can still proceed on the basis that “woman” is a particular category defined as above. Even if “woman” is then a category with three “essential” properties — i.e., “adult”, “human”, and “female” with a faint question mark attached to the latter — instead of one essential property as with “vertebrate”. Starting off on that foot, starting off from that definition for “woman”, we can then see where many people are falling into the “pits”, if not bottomless rabbit-holes, created by their misperceptions of the nature of categories.

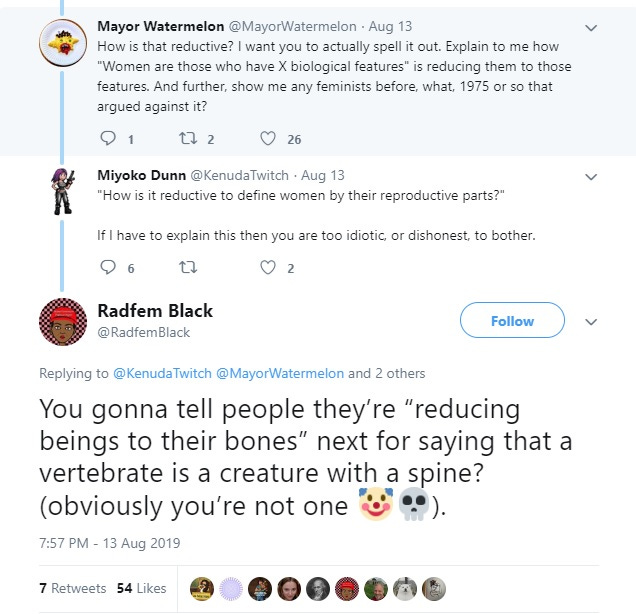

As something of a stark illustration of those pitfalls and misperceptions, consider this tweet exchange and, in particular, the rather brilliant tweet and equally illuminating analogy from “Radfem Black”:

The whole “conversation” there seems to turn on two very different and quite antithetical definitions for and conceptions of “woman”. Apparently “Mayor Watermelon” and “Radfem Black” subscribe to the standard definition, the one that “Posie Parker” commendably emblazoned on buildings and billboards all across the UK, i.e., “adult human female (sex)”:

Talk about “Mene, mene, tekel, upharsin” — the writing on the wall for transgenderism, if not for much of feminism itself. But the second and more problematic definition of “woman” is basically as a gender which apparently or potentially encompasses anyone who exhibits any trait at all — like transwomen with their ersatz breasts and neovaginas or still functional penises and testicles — that might bear some passing resemblance to any traits typical of actual “adult human females (sex)”.

For example, both Wikipedia and Merriam-Webster endorse the use of “woman” as a gender, even if the links to “woman” that they provide in the following go to primary definitions as “adult human female”:

Most cultures use a gender binary, in which gender is divided into two categories, and people are considered part of one or the other (boys/men and girls/women); ….

Among those who study gender and sexuality, a clear delineation between sex and gender is typically prescribed, with sex as the preferred term for biological forms, and gender limited to its meanings involving behavioral, cultural, and psychological traits. In this dichotomy, the terms male and female relate only to biological forms (sex), while the terms masculine/masculinity, feminine/femininity, woman/girl, and man/boy relate only to psychological and sociocultural traits (gender).

Rather remarkably clueless, if not actually quite stupid, of both to clearly differentiate between sex and gender — commendable in itself — yet turn around and then define the differentia of gender — e.g., “man” and “woman” — as the “intersections” of the three categories of sex (male or female), species, and age. They’re basically saying, to begin with, that sex and gender are different but then say, in effect, that they’re the same; part and parcel of the outright insanity of “gender” — all predicated on a too-common confusion between categories and identities:

But that conflict is particularly “problematic” since the sexes are defined only on the basis of reproductive functions — as indicated above; they say absolutely diddly-squat about what “psychological and sociocultural traits” might clearly differentiate between “men” and “women”, about which traits might be unique to, and definitive of those two categories as genders.

Hard to imagine a more incoherent and quite unscientific concept than “gender” — for which we have much of feminism to “thank”. We haven’t seen its like since phrenology, mesmerism, and homeopathy — all thrown in together in a quite toxic and mephitic witches’ brew. Though, as I’ve argued in my first post, there may be some merit in the concept, at least as a synonym for personalities and personality types — of which there are billions and billions.

However, all of that is somewhat beside the point that “Radfem Black” underlined with her rather brilliant analogy: “woman” — like “vertebrate”, like “teenager”, like “female” — is simply the name for a category and members of it, attached to which are some more or less explicit specifications for the “membership dues”, i.e., being adult, human, and female — even if there’s a faint question mark hidden in the latter. But there’s no magic in the word, no immutable or ethereal essence that bestows membership. If people can meet those membership requirements then they can “wear the colours” of that “gang”. And if they don’t meet them — like transwomen, “bepenised” or de-penised — then they can’t.

Unfortunately, many people like “Miyoko Dunn” have clearly turned the name for the category “woman” into an identity — a “triumph” of reification over reason and logic. To them, “woman” is apparently a label that symbolizes, not just the entirety of a person — which would be bad enough since it seems to make all “women” into no more than peas in a pod without any individuality at all — but a manifestation of some mythical je ne sais quoi essence. Equally unfortunate is that it is not just transgender activists who make category names into identities since many feminists — like Maya Forstater — do likewise with their insistence, in a mantra of their own, that “sex is immutable” (it ain’t).

Clearly, neither “woman”, nor “female” nor “vertebrate” are identities — much less ones based on any “mythic essences”. They are all, pure and simple, simple categories, membership in which is dependent on the possession of more or less distinct and readily quantifiable properties — which are often quite transitory as with “teenager”. Seems rather important to be clear on the differences between the properties that define and determine category membership, on the one hand, and the somewhat arbitrary names we give to those categories, on the other hand. Losing sight of those profound differences can often lead to no end of “cognitive distortions” and to unnecessarily acrimonious and unproductive “debate”.

Certainly teenager is age limited (as are baby, infant, middle-aged and elderly, to less well defined degrees) because it is an age category, and that doesn't equate to an argument that sex must also be age-limited. As I understand it, you stick so strictly to the one criterion for defining sex—production of large or small gametes—that you feel infants, children and post-climacteric quondam women are to be considered sexless. Might we not solve that problem by indicating that sex is defined by the gametes you make during your reproductive years? A girl is a woman-to-be, and a crone an honorary woman still? And the same thing for boys (old men are still producing small motile gametes so I assume you have no issue with their title). I'm not a taxonomist, and I don't think that practical people need be reductionist about diagnosing sex. We can live with the idea that the sexes in normal humans are characterised by the gametes they make when of reproductive age, the chromosomes they have, and by their endocrine functions.

But in the bigger picture, what is the point of this hair-splitting? You don't like the idea of sex being immutable, but why is this? You are not suggesting, I know, that what we used to call a sex-change surgery does anything of the sort, and we all know that. I find it curious, by the way, that the folk who now refer to themselves as 'transgender' still want what is called 'sex-re-assignment surgery.' There is enough confusion about sex and gender without adding to it by claiming sex is a transitory category to which we belong only for part of our lives. Unless, Steers old friend, you are subconsciously trying to assist the trans activists in muddying the waters further. I don't think you are, so what is your purpose?

Hi Steersman,

I found this after reading your comments and discussions with others in the comments sections of various articles in Reality's Last Stand. I have some comments and a question.

First the comments:

Regarding Maya Forstater and her stated belief in the immutability of sex in humans, I posit there may be a simpler explanation for that stated belief than it being based on some magic essence, namely that "immutability" may be short hand for the idea that you can't change men into women or vice versa.

The medical treatments and surgery that trans people may undergo to look like members of the opposite sex, at best give one the external appearance of that sex. Even if you define male / female in terms of possession of relevant reproductive anatomy / structures rather than functioning gonads this seems true to me. Even the most complete medical transition will not e.g. give a transwoman a womb, ovaries or uterus, whilst the surgically constructed neo-vagina isn't a real vagina.

Another comment: we routinely refer to people / classify them as boys or girls, men or women, without knowing the status of their gonads - it seems to me this reflects the fact that human bodies come in 2 broad classes (admittedly with a lot of variation in those classes) - one associated with small gamete production (given mature, healthy reproductive organs), the other associated with large gamete production (given mature, healthy reproductive organs). I realise this is moving into 'family resemblances' territory, but it also seems to me a reality of being human. We can look at someone and, based on their collective physical characteristics, classify them as male or female in a way that correlates well with the role in reproduction they would play if/once they have functioning gonads. This may explain why some people reach for a definition of sex that doesn't require functioning gonads. Note that we often sex animals in a similar manner - e.g. after neutering a male cat we will likely still refer to the cat as 'he' or 'him'.

This leads me to my question: how would you define the categories of boy and girl, given that (pre-pubescent) children are sexless under the strict biological definition of sex you prefer?